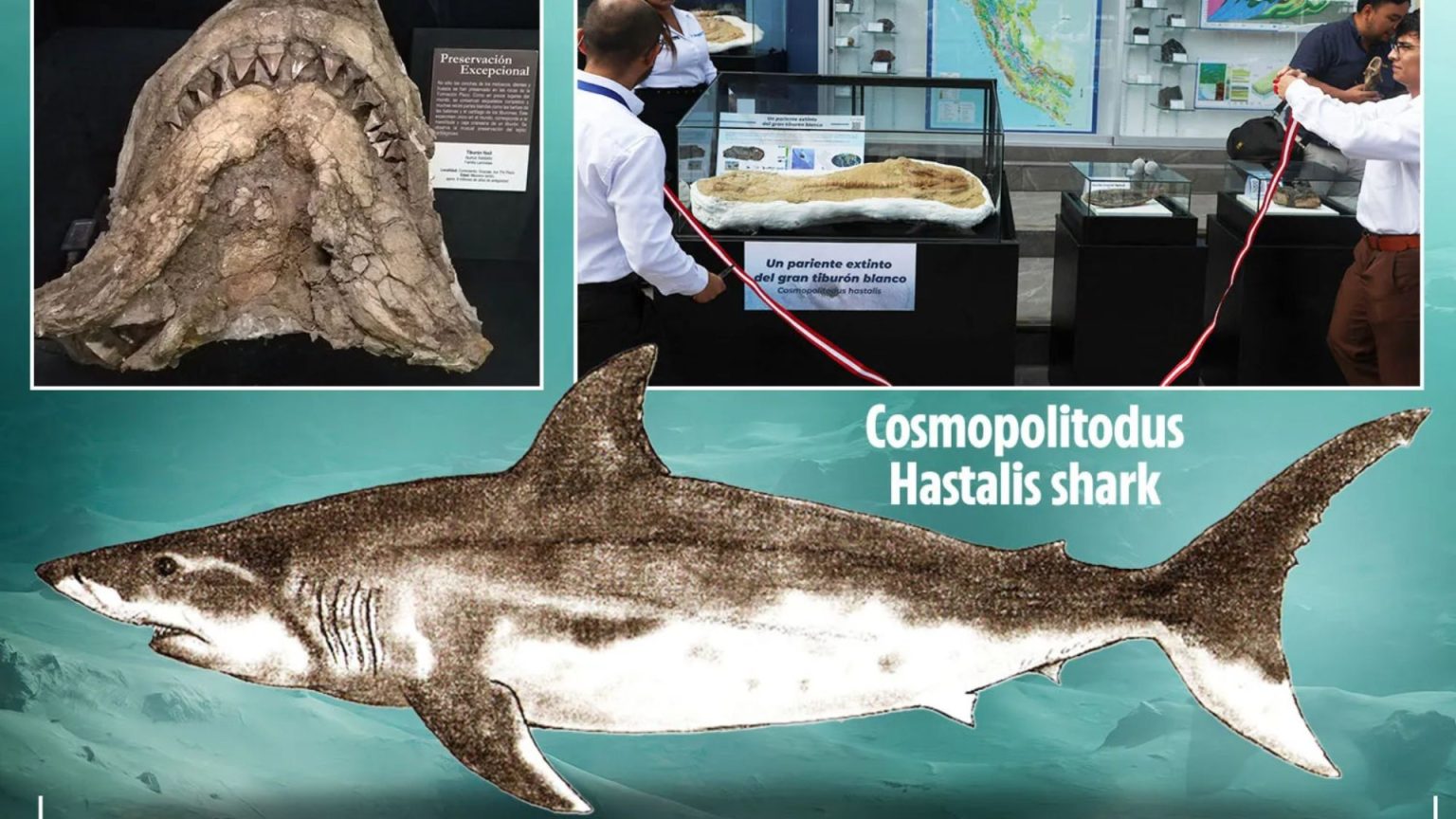

The arid Pisco basin of Peru, a region renowned for its rich paleontological discoveries, has yielded another remarkable find: the exceptionally well-preserved fossil of a nine-million-year-old shark, believed to be an ancestor of the modern great white. This massive predator, identified as Cosmopolitodus hastalis, measured an estimated 23 feet in length, akin to a small boat, and possessed formidable teeth reaching lengths of up to 3.5 inches – significantly larger than the teeth of its modern counterpart. The discovery of such a complete shark fossil is a rare occurrence, offering invaluable insights into the evolution and behavior of these apex predators. This particular fossil, unearthed 146 miles south of Lima, represents the first juvenile specimen of C. hastalis discovered, indicating that the individual perished before reaching its full adult size.

The Cosmopolitodus hastalis was a dominant predator in the Miocene epoch, navigating the ancient seas and feasting primarily on fish, likely sardines, as anchovies had not yet evolved. Analysis of the fossil, including bite marks discovered on the bones of a fossilized Pliocene dolphin (Astadelphis gastaldii), reveals a hunting strategy strikingly similar to that of the great white. Evidence suggests C. hastalis attacked from below and behind, initially targeting the abdomen to inflict a swift, fatal blow. Subsequent bite marks near the dolphin’s dorsal fin suggest the prey rolled over while injured, sustaining further attacks.

The Cosmopolitodus hastalis fossil discovery adds to a growing list of significant paleontological finds in Peru, further solidifying the country’s reputation as a hotspot for ancient marine life. Previous discoveries include a ten-million-year-old fossilized crocodile found in central Peru and the skull of a giant, extinct river dolphin that inhabited the Amazon some 16 million years ago. These discoveries offer invaluable glimpses into prehistoric ecosystems and the evolutionary pathways of contemporary species.

The C. hastalis possessed an elongated snout, a characteristic shared by other piscivorous (fish-eating) sharks. While the modern great white boasts impressive size and hunting prowess, its ancient predecessor arguably dwarfed it in sheer scale. The discovery of the juvenile C. hastalis offers a unique opportunity to study the growth and development of these prehistoric sharks, comparing their features and adaptations to those of their modern relatives. The finding also emphasizes the importance of the Pisco basin as a repository of exceptionally preserved fossils, providing a window into Earth’s ancient past.

The Pisco basin’s unique geological conditions have facilitated exceptional fossil preservation, allowing researchers to study extinct species in remarkable detail. The C. hastalis fossil, with its near-complete skeleton and associated bite marks on prey, offers a rare glimpse into the predatory behavior and ecological role of these ancient sharks. This discovery contributes significantly to our understanding of the evolutionary history of sharks and the dynamics of prehistoric marine ecosystems.

Peru’s continued paleontological discoveries, including the C. hastalis fossil, the ancient crocodile, and the giant river dolphin, underscore the importance of paleontological research in reconstructing past environments and understanding the evolution of life on Earth. These findings also highlight the need for continued exploration and preservation of fossil-rich regions like the Pisco basin, which hold invaluable clues to our planet’s history and the fascinating creatures that once inhabited it. The ongoing research in the region promises further insights into the evolution of marine life and the complex interplay of species in prehistoric ecosystems.